Writing a CHIP-8 Emulator in Zig: Gitting Gud With Bits

Published on: 2025-03-20

Last blog post I talked about writing a basic Lexer in Zig and doing the Ziglings exercises. Maybe it is Stockholm Syndrome, but I decided to move on from it for a bit, but I kept thinking about Zig.

Turns out that I really enjoyed working with Zig. I’ve been in Go and TypeScript land for my other project at the moment, so I wanted to clear my head and have some fun again.

Emulation Station

I was out at a brewery with some friends a while ago and the topic of emulators got brought up. I’ve always been interested in emulation, but never really touched the topic. I did a little cursory research and talked with folks in various discords and it become clear to me that there was one very logical starting place for an emulator noob: CHIP-8.

The CHIP-8 has a storied history and years of tinkering from the programming and emulation community.

Truthfully, a CHIP-8 emulator isn’t really an ‘emulator’, but more of an interpreter or virtual machine. That being said, it practically doesn’t make much of a difference as a learning project. Some of the core concepts necessary to emulation are present, but with a much more gentle learning curve.

For example, the screen is just 64x32 and the ‘pixels’ can only be on or off. That’s really damn simple. No colors to worry about and small enough that it can be reasoned about with extreme ease in my opinion.

Did I mention that the entire process is extremely well documented? Each part of the CHIP-8 emulator is well-documented, discussed, and understood. Even where there are varying implementations (for certain opcodes, for example), it’s pretty well understood.

First Steps

First simple step was deciding how to handle rendering the CHIP-8. A lot of people tend to gravitate to SDL and for good reason. But since Zig supports importing and building C libraries, there are lots of options. I’m pretty deep in the independent game dev world, so I keep hearing good things about raylib; it also happens to have a pretty solid and actively maintained zig binding.

Getting it set-up quickly was exceptionally easy:

pub fn main() !void {

const screenWidth = 1024;

const screenHeight = 512;

const pixelWidth: comptime_int = screenWidth / 64;

const pixelHeight: comptime_int = screenHeight / 32;

rl.initWindow(screenWidth, screenHeight, "chip-8 in zig");

rl.initAudioDevice();

rl.closeAudioDevice();

defer rl.closeWindow();

// ... blah, blah, blah, you get the idea

while (!rl.windowShouldClose()) {

rl.beginDrawing();

defer rl.endDrawing();

rl.clearBackground(rl.Color.black);

rl.drawRectangle(screenWidth / 2 - pixelWidth,

screenHeight / 2 - pixelHeight,

pixelWidth, pixelHeight,

rl.Color.white

);

}

}CPU Module Time

Okay, cool… we have a window with the correct aspect ratio. And it can render whatever static stuff we tell it to manually. Neat, but useless.

Next I had to make a CPU module to represent the interpreter itself. Is it really a CPU? Not exactly, but it’s similar enough and only three characters, so let’s roll with the name. Here’s the initial set up:

const std = @import("std");

const Self = @This();

// 4kb of memory.

memory: [4096]u8,

// Display is essentially just 64*32 on or off pixels. Could also be

// represented as [64][32]u8 as well.

display: [32][64]u8, // [y][x]u8 for graphics

// Opcode stores the two u8 memory addresses as one 16-bit opcode

opcode: u16,

// Program Counter (PC) which points to current instruction (u16)

pc: u16,

// Index register to point at memory locations:

ir: u16,

// Stack & Stack Pointer

stack: [32]u16,

sp: u16,

// Timers

delay_timer: u8,

sound_timer: u8,

// Variable Registers - 16 bytes 0 - 15

registers: [16]u8,So there are some paradigm shifts from the last time I wrote Zig if you can’t tell. I think you’ll find that this is more “idiomatic” Zig. First of all, each module itself is just a struct. That’s it… so each definition is just commma-separated.

The whole const Self = @This(); is a slightly hacky looking, but totally valid

Zig-ism to create a reference to the internal struct. I’m not going to cover

everything, but let’s touch on the important stuff:

- Each CHIP-8 Program 4kb of memory that you load in. Just an array of

u8integers. Most notably is that addresses0x000up to0x200are reserved by the CPU. This is where, traditionally, the CHIP-8 emulator itself would live as far as I understand. Now, we just leave it mostly blank aside from some addresses to store font sprites. - We touched on this earlier, but the

displayis just 2048 pixels, right? You could just dump them in a single array and call it good, but I find it a little hard to reason about. Instead, I chose to opt for a 32 by 64 matrix. When you’re dealing with a finite data-set, there’s really no overhead cost to doing so. 2048 is 2048 is 2048, so make it work in a way that makes sense for you. - The

opcodeandpc(program counter) are odd. The opcode is just two selected memory addresses glued together as au16. The program counter is a pointer, stored as au16(keep in mind the number of memory addresses available to us). This will be important later. - I’ll skip over the stack, stack pointer, timers, and registers. Pretty simple

stuff, with the only note that the

0xFregisters is special and should be used for instruction flags.

Phew, set-up is out of the way. We’ll skip the initialization method for now…

RTFM: Instruction Time

All the setup is basic stuff. The heart and soul of CHIP-8 emulation? The instructions themselves.

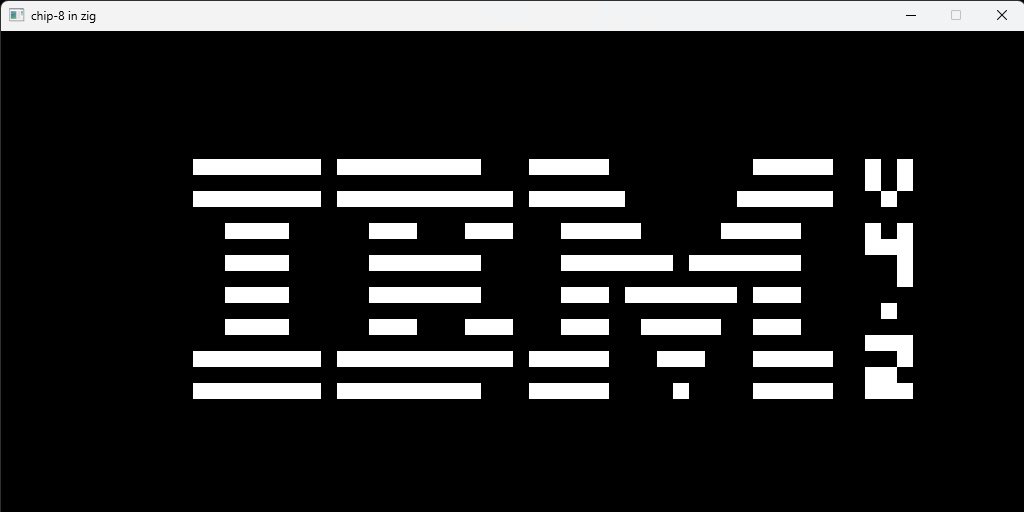

Fortunately, the instructions are insanely well documented: the defacto reference from Cowgod and Tobias V. Langhoff’s code-free guide will do the trick nicely for explaining any of the more cryptic details. Tobias Langhoff’s in specific suggest starting with getting the IBM logo ROM. This simple little program just renders the IBM logo on the screen and verifies that you have the basic instructions and loop themselves working.

Here are the requisite instructions:

0x00E0- Clear the Screen0x1NNN- Jump toNNN0x6XNN- Set registerVXtoNN0x7XNN- AddNNtoVX(no overflow!)0xANNN- Set index register toNNN0xDXYZ- Draw a sprite of heightZat[VY][VX]screen position.

That last one… yeah, it’s a doozy if you couldn’t tell already.

Less Yap, More Code

Each CPU cycle has three steps:

- Fetch

- Decode

- Execute

We’re rolling decode and execute into one step because it frankly makes sense. Just to get it out of the way, let’s make fetch a thing:

pub fn fetch(self: *Self) void {

const first_half = @as(u16, self.memory[self.pc]);

const second_half = @as(u16, self.memory[self.pc + 1]);

self.opcode = @as(u16, (first_half << 0x08) | second_half);

self.pc += 2;

}Dummy simple, huh? It’s what I described a little earlier… Just glue the contents of the two different memory addresses together, and bump the program counter up two. Then it’s time to decode the opcode and execute it. First things first, let’s isolate all the pieces of the opcode:

pub fn decode(self: *Self) void {

const nibble: u4 = @intCast(self.opcode >> 12);

const nnn: u12 = @intCast(self.opcode & 0x0FFF);

const x: u4 = @intCast((self.opcode & 0x0F00) >> 8);

const y: u4 = @intCast((self.opcode & 0x00F0) >> 4);

const z: u4 = @intCast(self.opcode & 0x000F);

const kk: u8 = @intCast(self.opcode & 0x00FF);

// To continue further down...The opcode we ‘glued’ together early has four u4 ‘nibbles’. Each single

nibble, or combination of nibbles, can mean something different in the different

instructions. Let’s cover each one:

nibbleor is the first four bits of the opcode. This will determine which instruction we run and we will switch on it. That’s more or less the whole purpose of this one. NB: My naming of this is unconventional and we’ll get into that later.- ‘NNN’ are the last bits of the opcode and typically represent a pointer to a memory address we want to check later.

x,y, &zare the first, second, and third set of four bits from ‘NNN’. They will be used in various bitwise, register store, and drawing operations. Keep in mind this largely works because our stack and register will largely fit into au4int. Typicallyzis referred to asnornibble, but I find that counter-intuitive.- Finally,

kk. It’s only used a few times, but will be important for some operations with memory and registers.

This are the glue for the entire thing: aside from initially getting the bits out, there are only a few significantly difficult parts of this project. The difficulty spike for me here was that I hadn’t really done a large amount of bitwise operations.

If you have ever struggled reasoning about bitwise operations, I highly recommend trying this project (and specifically this part) out.

Anyway, here are the necessary instructions to make the IBM logo work:

switch (nibble) {

0x0 => {

switch (nnn) {

0x0E0 => {

// Clear the display

for (0.., self.display) |y_pos, row| {

for (0.., row) |x_pos, _| {

self.display[y_pos][x_pos] = 0x0;

}

}

},

// Other stuff...

else => {

return;

},

}

},

0x1 => {

self.pc = nnn;

},

// Opcodes 2 through 5 aren't needed yet.

0x6 => {

self.registers[x] = kk; // set register x to kk

},

0x7 => {

self.registers[x] += kk;

},

// 0x8 is a doozy, but not necessary for the IBM logo.

0xA => {

self.ir = @as(u16, nnn);

},

// Yeah... 0xD is brutal...

0xD => {

const vx = self.registers[x];

const vy = self.registers[y];

self.registers[0xF] = 0x0;

var i: usize = 0;

while (i < z) : (i += 1) {

const spr_line = self.memory[self.ir + i];

var col: usize = 0;

while (col < 8) : (col += 1) {

const sig_bit: u8 = 128;

if ((spr_line & (sig_bit >> @intCast(col))) != 0) {

const x_pos = (vx + col) % 64;

const y_pos = (vy + i) % 32;

self.display[y_pos][x_pos] ^= 1;

if (self.display[y_pos][x_pos] == 0) {

self.registers[0xF] = 1;

}

}

}

}

},

else => { // ... You get the idea, right? },

}As I’m sure you can tell, it’s all insanely simple… aside from 0xD!

Truthfully, nothing too bad is even happening in the draw instruction, it’s just

a little hard to reason about. In so many words you want to:

- Grab the values of

vxandvy. - Flip

vfto 0. - Then loop over the size of

zwhich represents the sprite height. - XOR the pixel at the current location if it should be turned on.

- If the pixel got turned off, a collision happened and you should flip

vfon!

It Works!

That’s really it. As a result we get the absolutely boring, but milestone achievement:

Truthfully, there’s a fair chunk left to do, but most of the heavy lifting is officially done. The keyboard and inputs need to be handled as well as a variety of remaining instructions. But the bones are in place for a solid implementation.

Until next time, may yours structs be beautifully aligned!

P.S. Here’s the repository on GitHub in case you want to take a peek.